CNC Turning:Processes, Machines, Operations, and CNC Turning Programming Explained

CNC turning is a core machining process used to produce precise cylindrical and rotational parts across industries such as automotive, aerospace, and medical manufacturing. By removing material from a rotating workpiece under computer numerical control, CNC turning delivers high accuracy, repeatability, and production efficiency that manual turning cannot match.

This article explains how CNC turning works, the machines and operations involved, and when it is the right manufacturing choice. It also introduces CNC turning programming, outlining how G-code controls turning operations and ensures consistent machining results.

What Is CNC Turning?

CNC turning is basically a way to shape a part by spinning it while a cutting tool removes material. The workpiece sits in a chuck or collet and rotates, while the tool moves along the X and Z axes to create the shape you need.

It’s perfect for making round or cylindrical parts—like shafts, bushings, threads, or grooves. Because the whole process is controlled by a computer, you get parts that are consistent, accurate, and repeatable, whether you’re making one piece or a hundred.

Compared with manual turning, CNC turning takes the guesswork out of cutting. And unlike milling, where the tool spins and the part stays still, turning works best when the part’s geometry is mainly round or rotational.

How CNC Turning Works

CNC turning is actually pretty straightforward once you see it in action. The basic idea is simple: the part spins, and a cutting tool moves against it to take away material until it has the shape you want.

Here’s how it usually goes:

1.Design the part in CAD – Everything starts with a digital 3D model of your part.

2.Plan the toolpath in CAM – Software figures out the best way for the tool to move and cut.

3.Generate the CNC program – This turns the plan into instructions (G-code) the machine can follow.

4.Set up the machine – Clamp the workpiece in the chuck and make sure the right tools are loaded.

5.Start turning – The spindle spins the part while the tool moves along the X and Z axes.

6.Check your part – Measure it to make sure it’s accurate and smooth.

The cool thing is the computer handles the cutting. That means every part comes out consistent and accurate, and you don’t have to rely on someone’s steady hand.Some lathes can do more than just X and Z moves. Multi-axis machines let the tool tilt or rotate,so you can make more complex shapes without stopping the spindle. But for most jobs, the standard X and Z movements do the trick.

CNC Turning Machines

CNC turning is carried out on specialized lathes that rotate the workpiece while cutting tools remove material to create the desired shape. The design of the machine plays a crucial role in precision, efficiency, and repeatability. Every component, from the spindle to the control system, contributes to how accurately and consistently the part is produced.

Main Components of a CNC Turning Machine

The spindle and chuck are at the core of the machine. The spindle rotates the workpiece, and it must be stable and precise to maintain dimensional accuracy. The chuck holds the part securely, preventing any slipping during cutting, which is essential for consistent results. The tool turret holds multiple cutting tools and rotates to bring each tool into position as needed, enabling several operations to be performed on the same part without stopping. The bed and guideways provide a stable, smooth surface for the turret and tool to move along, ensuring accuracy in every pass. The CNC control system acts as the machine’s brain, interpreting G-code and coordinating spindle speed, tool position, and feed rates. Coolant and chip evacuation systems keep the cutting area cool, reduce tool wear, and remove chips, preventing interference with the machining process.

Types of CNC Turning Machines

There are several types of CNC lathes, each suited to different parts and production requirements. Basic two-axis CNC lathes are widely used for standard cylindrical components like shafts, bushings, and threads. CNC turning centers are more advanced, often equipped with additional axes or live tooling, which allows milling, drilling, or slotting operations without removing the part, improving efficiency and accuracy. Swiss-type lathes are designed for small, slender parts and support the material close to the cutting area, reducing deflection and achieving higher precision, which is why they are commonly used in medical, aerospace, and electronics applications. Dual-spindle and multi-spindle machines are tailored for high-volume production, allowing multiple parts to be machined simultaneously or complex operations to be completed faster, making them ideal where speed and consistency are critical.

CNC Turning Operations

Now that we’ve covered the machines and their components, it’s time to look at what they actually do. CNC turning isn’t just about spinning a piece of metal or plastic—it’s about shaping it with precision through a variety of operations. Each operation has its own purpose, whether it’s forming the basic shape, cutting threads, creating grooves, or adding texture. Understanding these operations helps to see how a part goes from raw stock to a finished component.

Turning

Turning is the process of removing material from the outer surface of a rotating workpiece using a single-point cutting tool. It is used to reduce the diameter or create smooth cylindrical surfaces, forming the basic shape of shafts, rods, and other round components. Turning is often the first step in machining a part because it establishes the overall dimensions and surface finish for subsequent operations.

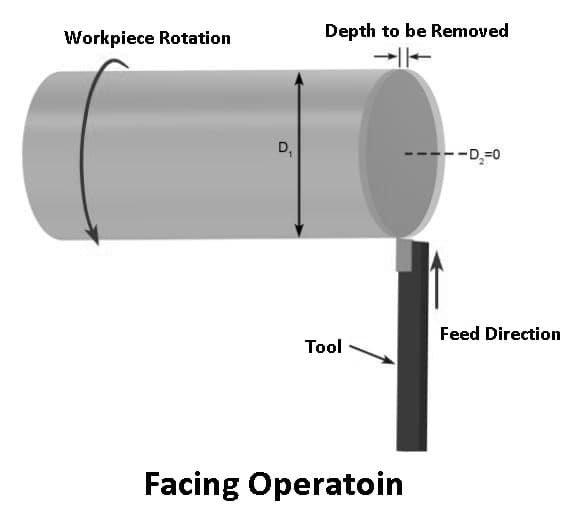

Facing

Facing cuts across the end of a rotating part to produce a flat or square surface. This operation is important for preparing the part for assembly, ensuring the ends are perpendicular to the axis, and creating a clean finish for further machining steps. Facing can also correct minor irregularities from previous operations or from the raw stock.

Grooving

Grooving creates narrow recesses or slots on the surface of a rotating workpiece. These grooves can serve functional purposes, such as retaining rings, O-ring seats, or snap rings, or they can provide design features. The tool is fed into the part to cut a groove of precise width and depth, and the CNC controls ensure accuracy and consistency.

Thread Cutting

Thread cutting produces helical grooves on the internal or external surface of a part to form threads. This operation is essential for screws, bolts, and threaded shafts, and the CNC program controls pitch, depth, and profile to achieve accurate, repeatable threads suitable for assembly.

Boring

Boring enlarges an existing hole while improving its dimensional accuracy and surface finish. This operation is commonly performed after drilling to ensure the internal diameter meets tight tolerances, which is critical when the part needs to fit bearings, bushings, or other precision components.

Parting / Cutoff

Parting, also known as cutoff, involves feeding a narrow tool into the rotating workpiece until it completely separates the finished part from the remaining stock. This operation is essential in production environments where multiple identical parts are machined from bar stock, and it requires precise control to avoid damaging the part or the machine.

Taper Turning

Taper turning forms a conical surface along the length of the workpiece by moving the cutting tool at an angle relative to the axis. This operation is used when parts need to fit into mating components with angled surfaces or for features such as tapered shafts. CNC control ensures the taper angle and dimensions are accurate and consistent.

Knurling

Knurling produces a patterned texture on the surface of a part by pressing a tool into the rotating workpiece. This texture improves grip on handles, knobs, or threaded fasteners and can also serve aesthetic purposes. CNC machines allow precise control over the knurl pattern, spacing, and depth.

Materials for CNC Turning

| Material | Key Properties | CNC Turning Notes | Common Applications |

| Aluminum Alloys | Lightweight, corrosion-resistant, easy to machine | Moderate speeds, sharp tools, coolant recommended | Aerospace, automotive, consumer products |

| Steel & Stainless Steel | Strong, tough, corrosion-resistant (stainless) | Slower speeds, robust tools, consistent feeds; stainless prone to work hardening | Structural parts, machinery, medical devices |

| Brass & Copper Alloys | Highly machinable, good heat conduction | Continuous chips, effective chip removal, can cut faster than steel | Fittings, electrical components, decorative parts |

| Titanium & Superalloys | Strong, heat- and corrosion-resistant | Low speeds, specialized tools, careful feeds to avoid overheating | Aerospace, medical implants, high-performance components |

| Plastics & Engineering Polymers | Lightweight, corrosion-resistant, easy to shape | Low speeds, sharp tools, avoid melting or chipping | Mechanical components, medical devices, consumer products |

| Machinability Considerations | Varies by material hardness and structure | Dictates cutting speed, feed rate, and tool selection | Helps optimize tool life and surface finish |

| Impact on Tool Life & Finish | Hard or abrasive materials wear tools; soft/sticky can smear | Use proper tool coatings and CNC parameters | Ensures high-quality, consistent parts |

CNC Turning Programming Explained

After covering machines, operations, and materials, it’s time to look at the brain behind the whole process—the CNC program. CNC turning programming tells the machine how to move the cutting tools, control spindle speed, and execute operations with precision. A well-written program ensures efficiency, accuracy, and safety, while poor programming can lead to scrap parts, tool damage, or collisions. Understanding both the principles and the common codes is key for anyone working with CNC turning.

What Is CNC Turning Programming?

CNC turning programming is the process of creating instructions, often in G-code, that control the lathe during turning operations. These instructions define tool paths, spindle speed, feed rates, and the sequence of operations. Programming can be done manually, writing each line of G-code, or generated using CAM (Computer-Aided Manufacturing) software. Manual programming is useful for simple parts or custom adjustments, while CAM-generated code is faster and more efficient for complex geometries and production runs.

Common G-Code and M-Code Used in CNC Turning

CNC turning relies on G-codes to control tool movement and M-codes to manage machine functions. Here’s a quick reference for the codes most commonly used in turning:

| Code | Function | Typical Use in Turning |

| G00 | Rapid positioning | Move the tool to start point without cutting |

| G01 | Linear interpolation | Perform a straight cut along the workpiece |

| G02 / G03 | Circular interpolation | Cut arcs or helical profiles, e.g., threading grooves |

| G96 / G97 | Constant surface speed / fixed RPM | Control spindle speed for consistent finish |

| G50 | Spindle speed limit | Protect the tool and workpiece |

| M03 / M04 | Spindle rotation start clockwise / counterclockwise | Set spindle rotation direction |

| M05 | Spindle stop | Stop spindle rotation safely |

This table makes it easy to see which codes are used for specific operations and how they affect machining.

Programming Turning Operations

Different turning operations require specific programming cycles. Facing and turning cycles control how the tool removes material along or across the axis. Threading cycles specify pitch, depth, and path for cutting internal or external threads. Grooving cycles create narrow recesses or slots, and roughing and finishing passes manage the bulk material removal versus final surface finish. Properly programming these cycles reduces tool wear, maintains dimensional accuracy, and improves overall efficiency.

Programming Best Practices

Good CNC programming goes beyond knowing G-code. Tool offsets must be managed correctly to maintain part accuracy. Collision avoidance ensures both the machine and workpiece remain safe. Optimizing cycle time improves productivity without sacrificing quality. Finally, program verification and simulation in CAM or on the machine control screen help catch errors before cutting begins, reducing the risk of mistakes and ensuring consistent, high-quality results.

CNC Turning Tolerances and Surface Finish

After discussing machines, operations, materials, and programming, the next step is quality. CNC turning tolerances and surface finish determine whether a part will fit and function as intended. Even small deviations can affect assembly, performance, and aesthetics, so understanding what affects precision and surface quality is essential.

Typical CNC Turning Tolerances

CNC turning can achieve very tight dimensional tolerances, often ranging from ±0.005 mm to ±0.05 mm depending on the material, machine, and operation. Tolerances indicate how much a finished dimension can deviate from the design specification. Parts with higher tolerance requirements usually need slower machining, precise tool offsets, and careful planning of cutting passes to avoid error accumulation.

Factors Affecting Dimensional Accuracy

Several factors influence the dimensional accuracy of a turned part. Machine rigidity and calibration play a key role, as vibrations or misalignment can cause deviations. Tool wear changes cutting geometry over time, impacting accuracy. Material properties, such as hardness and thermal expansion, also affect how a part reacts during cutting. Finally, programming and setup—spindle speed, feed rate, and workholding method—must be optimized to maintain precise dimensions.

Surface Roughness Options

Surface roughness, often expressed as Ra (average roughness), measures the texture of a machined surface. CNC turning can produce a wide range of finishes, from rough initial cuts (Ra 3.2–6.3 µm) to fine finishes (Ra 0.2–0.8 µm) for aesthetic or functional purposes. The choice of tool geometry, cutting speed, feed rate, and coolant all affect the final surface. Multiple finishing passes or specialized inserts can help achieve very smooth surfaces.

Inspection and Measurement Methods

To ensure parts meet specifications, inspection and measurement are critical. Common methods include micrometers, calipers, dial indicators, and coordinate measuring machines (CMMs). Surface finish can be measured with profilometers or contact/non-contact roughness testers. Regular inspection helps catch errors early, maintain quality, and ensure parts are within specified tolerances before assembly or shipping.

Advantages and Limitations of CNC Turning

CNC turning offers a variety of benefits that make it a popular choice for producing cylindrical parts, while also having limitations that engineers need to consider. Understanding both sides helps in choosing the right manufacturing method or planning secondary operations.

| Advantages of CNC Turning | Limitations of CNC Turning |

| High precision and repeatability, producing consistent parts across batches with minimal variation | Best suited for cylindrical or symmetrical features; not effective for flat, angular, or irregular geometries |

| Excellent surface finish, often reducing the need for secondary finishing operations | Internal features or complex multi-surface shapes may be difficult or impossible to reach with standard turning tools |

| Strong material versatility—can handle a wide range of metals and engineering plastics | High initial cost for machines, tooling, and setup, particularly for small shops |

| Efficient for medium to high volume production with fast cycle times and reduced labor | Requires skilled programming and setup; complex parts need precise toolpaths and expertise |

| Cost-effective in large runs due to automation, repeatability, and lower scrap rates | Not always flexible for frequent design changes or very small batch production runs |

| Reduced manual error and improved workplace safety through automation | Tool access issues and limitations in tooling variety compared with milling operations |

| Lower material waste compared to manual machining through optimized toolpaths and simulation | Significant waste can still occur in subtractive processes, especially for complex shapes |

CNC Turning Applications

CNC turning is used across a wide range of industries because of its precision, repeatability, and efficiency. In the automotive industry, it’s commonly used to produce shafts, gears, and bushings that require tight tolerances and smooth finishes. Aerospace applications rely on CNC turning for components like engine parts and landing gear pins, where accuracy and material integrity are critical.

Medical devices also benefit from CNC turning, producing surgical instruments, implants, and other small, high-precision components. Industrial machinery uses turned parts such as spindles, rollers, and couplings to ensure reliable operation. Even in electronics, CNC turning helps create connectors, housings, and specialized components that demand consistent dimensions and surface quality.

CNC Turning vs Other Machining Processes

CNC turning is highly efficient for creating cylindrical parts, but it isn’t always the only option. Understanding how it compares to other machining processes helps engineers choose the right method for each application.

When compared to CNC milling, turning excels at producing round or tubular shapes with high precision and fast cycle times. Milling, on the other hand, is better suited for flat surfaces, pockets, or complex 3D geometries that turning cannot easily handle.

Swiss machining offers extreme precision for small, intricate parts, often with very tight tolerances and long slender features. While CNC turning can handle many similar components, Swiss machines provide advantages in extremely small diameters and multi-spindle efficiency for high-volume production.

Grinding is a finishing process rather than a primary material removal method. CNC turning can produce the basic shape quickly, and grinding may then be applied to achieve extremely tight tolerances or ultra-smooth surface finishes.

Sometimes, combining turning and milling in a single setup is the best solution. This approach allows manufacturers to take advantage of turning for cylindrical features while using milling for flats, slots, or other complex features on the same part, reducing handling and improving overall efficiency.

Design Tips for CNC Turning

- Focus on cylindrical, symmetrical shapes: These are the easiest and fastest to machine, reducing cycle time and tool wear.

- Avoid unnecessary complex features: Extra setups or secondary operations increase cost and risk of errors.

- Optimize tolerances: Keep tolerances tight enough for function, but not excessively tight, to save machining time and reduce scrap.

- Design grooves and threads for standard tooling: Extreme sizes complicate programming and increase tool wear; standard dimensions improve repeatability.

- Consider cost-effective design: Minimize setups, use standard stock sizes, and reduce features that require additional operations.

Conclusion

CNC turning is a versatile and highly precise machining process, capable of producing a wide range of cylindrical parts across industries such as automotive, aerospace, medical, and electronics. From material selection and machine operation to programming and design considerations, understanding each aspect ensures high-quality results and efficient production.

Choosing the correct process for each part is critical. CNC turning offers speed, accuracy, and consistent surface finish, but its limitations—like difficulty with non-rotational geometries—mean that milling, Swiss machining, or combined processes may sometimes be a better fit.

By applying proper design principles, optimizing tolerances, and using well-planned CNC programs, manufacturers can maximize the benefits of CNC turning while minimizing cost, waste, and errors. With careful planning and execution, CNC turning remains a cornerstone of modern precision manufacturing.